THIS IMMIGRANT VOTED

The most expensive credit card purchase I’ve ever made was $725 to the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, and it was a charge that would change the course of my life. This was the price for my first step toward citizenship.

With it, I submitted my N-400, the 10-page naturalization form to prove that I was worthy to be a citizen of the country I’d lived in for just short of 20 years. It’s a form I’ve started and stopped countless times in the past. At 20, I became eligible to apply, yet I sat on the decision for six more years. I'd think, I should just wait until we can start the process as a family. Or, If I move back to the UK, I’ll just have to pay double the taxes. Or even, How do people afford this application fee?? (It wasn’t until 2015 that USCIS began accepting credit card payments). But one thing was clear; under this current administration, there was no more time to stall. And now, this administration is bumping up the price of admission for simply applying to be a citizen to $1,160—an 81% increase.

For some, you must compound that with the additional cost of having a lawyer represent your case, as my family did when we originally came here. We shame immigrants for not taking measures to become naturalized, and yet we make it harder and harder to do so, despite that fact that the majority of us were, at one point, immigrants ourselves. For my parents who had hoped earlier this year to follow my lead in citizenship, the pandemic and further bureaucratic delays will continue to keep their votes out of reach this election. Votes that could have made a difference in their small town in Texas. It hurts.

I so, so badly wanted the representation promised with taxation. I was infuriated by those who had the ability to vote and chose not to, or essentially threw their votes away. I’ve lived in apartments before where prior residents’ mail-in ballots were sent to my door. I’d look at the envelope, their name, and think, what if? Would they even miss it?

Since my family became green card holders in 2002, the government has had my picture, my fingerprints, my signature, my skin/hair/eye color, and even scans of my irises. They have known everywhere I have ever lived and every job I’ve ever held. In turn, they gave me the opportunity to grow up in this country, and pay $540 every 10 years to have that right renewed. Any time my brother or I had a brush with bad behavior, we were reminded that our place here was not guaranteed. Freshman year of high school, I was joyriding in the back of a friend’s convertible, pulled over going 100+ mph. And besides the obvious danger of the situation, I was presented with a new vulnerability; any blemish on my record would make it that much harder to prove I deserved to be here. Anything more drastic could lead to my deportation to a place I hardly knew anymore.

This disconnect of being raised in the U.S but never fully feeling American made me especially cynical of U.S. politics. There’s nothing quite like sitting through your first Pledge of Allegiance, aghast at the collective reciting, but you catch on as you desperately try to assimilate. Every elected official I’d ever known seemed so far removed from their immigrant background and any empathy tied to it, whether Republican or Democrat. I don’t blame them; being born abroad, first generation, or even faintly pro-immigrant can be political suicide. It’s almost as if your legitimacy and allegiance can immediately be called into question if you can’t trace your lineage back to the founding fathers. Any foreignness is seen as a red flag. Consider the conspiracy theories around Obama’s natural-born right to presidency; these rumors spurred essentially because he wasn’t white and didn’t have a traditional English name. Then examine Ted Cruz, who was indeed born in a different country, yet no one challenged his claim to presidential candidacy.

To this point, I never felt truly represented, and learning about America’s dark past made me feel the need to distance myself even more. (Note: Great Britain also has such a brutal imperialist history, but we spent only about two weeks studying it in school.) A big part of me longed for the motherland we’d left behind, and I wondered whether I’d feel more complete there. I had an idealized version of my head of what it would be like to live there where I belonged. But the older I grew and the more time I spent abroad, the more I realized I was more American than anything else. This was my home, and it was about time to have a voice in how it was run.

Marching to the Utah State Capitol. Photo by Tamarra Kemsley.

In 2017, following Trump’s “Muslim ban”, I marched with friends in Salt Lake City in a rally for refugees and immigrants. I walked alongside my friend Nicole’s mother, who had come to the U.S. as a refugee from Poland. I shared my current situation with her which she met with wide, sobering eyes. She warned me that I shouldn’t wait another day because we had no idea what this administration would do next. That was my first real “Oh shit” moment—that without even realizing, I was marching for my own right to reside here. I recognized that even with a green card, I wasn’t as safe as I thought.

Fast forward a year. I conceded to the cost and dug deep into the N-400. The form makes you list every residence you’ve lived at for the past 5 years. You must also list every time you’ve left the country, and for how long. There are questions like, Have you ever tried to overthrow a government? Have you ever been a prostitute? Are you an active member of the communist party? Between March 23, 1933 and May 8, 1945, did you work with the Nazi government of Germany? And my favorite, Have you ever been a habitual drunkard? I can’t make this up. All these questions can be dealbreakers.

You must list any association, club, society, etc. that you have ever been a part of, and no matter your gender, you must agree to bear arms or provide non-combative services in the armed forces. If you disagree, you must explain and provide documentation to back your case.

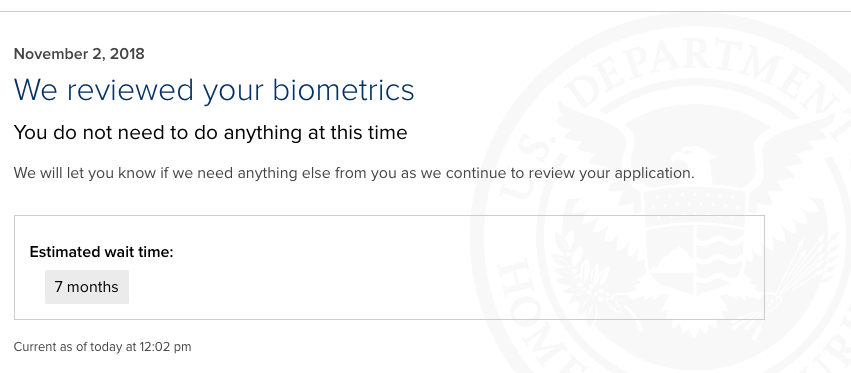

Once the form is submitted, your next step is a biometrics appointment where they once again take your picture, fingerprints, and signature. To enter the building for these steps, you must go through a metal detector and keep all electronics off for the entire duration. Then you wait (and wait, and wait…) for your interview, which includes your English comprehension test, a review of your application, the results of a thorough background check, and of course, the famous civics exam. This was the first exam I’d studied for in years, and arguably the most important test of my life. There are 100 questions to study, 10 of which are asked. You must answer at least 6 correctly. If you fail, you only have one more chance to retry.

Can you name the U.S. territories? How long does a U.S. senator serve? How many members are there in the House of Representatives? What are two cabinet-level positions? Who wrote the Federalist Papers?

If you’re stumped on any of these, don’t worry (unless you’re an immigrant). Apparently two-thirds of Americans would fail this test. Even with the kindest of interviewers, it’s a nerve-wracking process. But being told that you’ve passed… It’s the biggest sigh of relief I’ve had in my life.

Strutting to accept my naturalization certificate.

The following year, my first oath ceremony was canceled due to snow (thanks, Vermont). For the second, I asked two of my closest friends, Anna and Jackie, to attend as my surrogate family (and even borrowed Jackie’s blazer for the event). It’s surreal, taking a long lunch from work to become an American citizen. And honestly, it was a moving, emotional experience, standing in the courtroom pews with two dozen brand new Americans. The judge spoke to the incredible impacts immigrants have made in our country, from monumental inventions to philanthropic efforts to medical and scientific discoveries, and shared how we too have the power to better our nation. I was one of two white immigrants seated, and the only native English speaker. Even in Burlington, I was surrounded by people from Nepal, China, Papua New Guinea, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Chile, so many different places and different walks of life.

The Oath of Allegiance to swear us in as citizens.

It’s this realization at every step of the process that’s made me check my incredible privilege. Growing up, people were always shocked to hear I wasn’t a citizen because 1) I speak and sound fluently American, and 2) my skin is white. They had no reason to question my nationality because of those facts. There were lots of things new to my family that I’d figured out myself, paving the way for my younger brother: SATs, driving exams, applying to college, securing student loans, and now, citizenship. I can’t imagine approaching these rites of passage with additional intersections stacked against me. At the mildest inflection of an accent or tint of melanin, my nationality could be doubted. Instead, unintentionally, my white skin became camouflage for me to move through a highly inefficient and, at times, very subjective system with relative ease. It felt like every person next to me that day worked harder to get there and yet at this moment, we were all equals. There would always be other places we were from, but no longer other places we called home. By becoming citizens, we’d resigned our prior allegiances and embraced this country as our own with the hope that it would embrace us too.

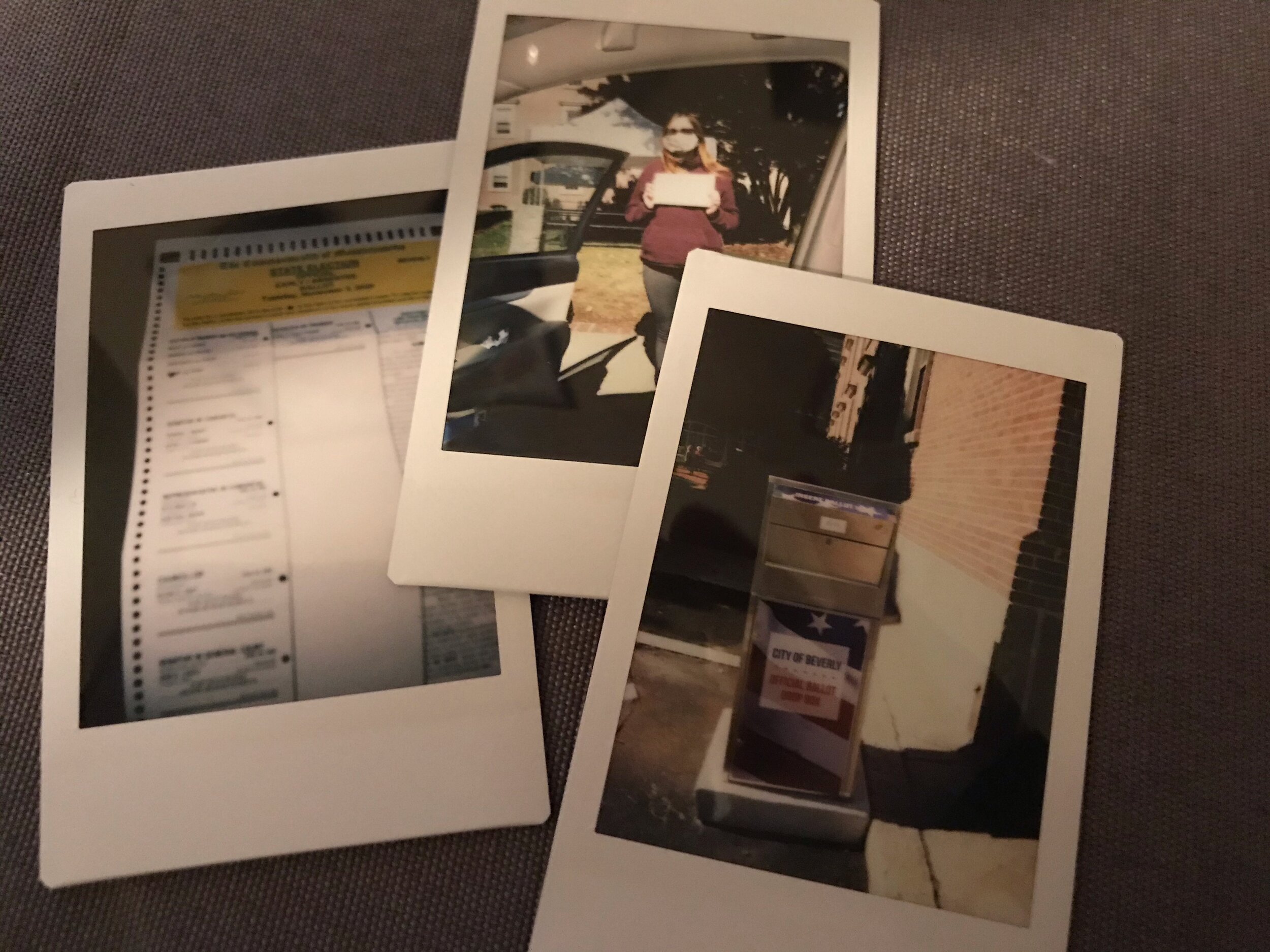

On October 17th, 2020, I voted in my first presidential election. I am the first in my family to do so. Pitt and I dropped our ballots directly into the ballot drop box, with its bright stars and stripes, and all around, people were doing the same. People were lined up at the City Hall polls next door for early voting. Spirits were high, even if we’re not sure what will happen come two weeks' time. And with so many things canceled or postponed this year, I can’t find the words to describe this feeling. Fulfillment? Relief? Maybe even pride? This year has been riddled with uncertainty and hopelessness, yet it felt so, so good to be part of something bigger.

Bottom line: Never, ever take your vote and voice for granted. Some spend so much of their lives chasing that opportunity only to have the carrot dangled further and further away. And yes, we’re all aware of the tangled mess of this country, and its flawed political and electoral system. But we still have power, and it’s never been more important to use it. After all, it’s your right. And now, it’s mine too.